How can Australian developers capitalise on the hydrogen export opportunity to East-Asian markets?

24 July 2023

The nature of the global low carbon hydrogen market is shifting as emerging demand from East-Asian markets enables export-focused projects globally. So far, the market has been characterised by limited near-term demand, with the projects operational today predominantly at demonstration level and co-located with end-use infrastructure (known as anchor demand). Emerging demand from East-Asia that is large-scale and import-focused is changing that. As such, a global market for the trade of low carbon hydrogen and related commodities (e.g. ammonia and methanol) will emerge in the medium term, initially driven by long-term structured origination and bespoke contracts. This development presents a crucial opportunity for Australia to kickstart its global hydrogen market and enable large-scale low carbon hydrogen export projects.

In this article, based on our work in this space across the value chain, we’ll explore 3 key questions (click to navigate to the relevant section):

- Making the market - how demand from South Korea and Japan is changing the nature of the hydrogen economy and creating opportunities for export

- The battle to capture this demand – which countries are best placed to become export powerhouses?

- How to win – what Australian developers can do to capitalise on these new opportunities

Making the market - demand from South Korea and Japan is changing the nature of the hydrogen economy and creating opportunities for export

South Korea and Japan are generating real movement in the hydrogen market. Both countries have established ambitious hydrogen targets and are looking to use hydrogen across a range of sectoral applications. To achieve these targets, imports will be crucial, with local development opportunities for hydrogen production limited by high renewable energy costs and land constraints. Japanese and South Korean developers and investors are therefore looking outside of their borders to develop the large-scale hydrogen production and export infrastructure needed to meet the demand of these East-Asian powerhouses.

But should we believe the hype around this demand? Two questions which are hotly debated in media are:

- How enduring will ambitious targets be?

- How soon is this demand coming?

The answer to the first point is linked to the long-term financial viability of hydrogen for decarbonisation of certain end-uses and the latter is driven predominantly by government and buyer appetite to support first-movers to establish a position in the global market. Both Japan and South Korea lack attractive alternatives for low-carbon generation or vehicle fuel, and both have a clear policy ambition to be market leading in this area, making them worthy of careful consideration by developers. So what has each country committed to in this space?

South Korea – hydrogen planned to supply a third of the country’s energy by 2050

South Korea has pledged to cut emissions by 40 per cent between 2018 and 2030, and to reach net zero by 2050. To achieve this, South Korea is seeking to become a leader in hydrogen utilisation, aiming for hydrogen to supply a third of its primary energy by 2050. By comparison, the most ambitious European country is aiming for 14% hydrogen in the energy mix. The government’s latest strategy plans target an increase in hydrogen consumption from about 220,000 tonnes in 2021 to 3.9 million tonnes by 2030, reaching 27.9 million tonnes by 2050. South Korea currently imports more than 90% of its energy and natural resources and a hydrogen economy will be no different, with the government expecting 82 per cent of targeted demand to be met by imports.

South Korea is focusing its initial hydrogen uptake on transitioning fossil-fueled vehicles and power generation. Baringa models the South Korean power market long-term through our South Korean wholesale electricity market report. This indicates that to achieve its net zero target, coal and gas generation in South Korea will decrease from 41% and 17% respectively in 2023 to 0% by 2050. Under a base-case scenario, coal and gas plants move towards co-firing of ammonia and hydrogen respectively from the early-mid 2030s, with ammonia making up around 5% of generation and hydrogen over 25% by 2050. If net zero targets are to be met in South Korea, ambitious hydrogen import targets will need to endure.

To enable these ambitious objectives, the South Korean government is supporting the development of port infrastructure, pipelines, storage for smoothing supply chains, and the development of three hubs that will focus on manufacturing hydrogen products. A tender announced in June for hydrogen-powered generation will see 650GWh of new plant announced in August. This is the first in a series of ongoing procurement events planned to stimulate 1.3 TWh of new build projects annually.

Japan – hydrogen market expected to boom from 2 Mt p.a. to 20 Mt p.a. by 2050

Emerging hydrogen demand from Japan tells a similar story. Japan’s latest Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) states the country’s aim of reducing emissions by 46% by 2030 against 2013 levels. Like South Korea, achieving this target will rely heavily on low carbon hydrogen imports, with renewable energy expansion constrained by inflated costs and land availability. The Japanese government aims to expand its hydrogen market from 2 Mt p.a. in 2020 to 3 Mt p.a. in 2030, followed by a 4-fold uplift 12 Mt p.a. in 2040 to 20 Mt p.a. in 2050 (as per the Green Growth Strategy ).

Japan and South Korea are closely aligned in their targeted development areas and use cases, prioritising the use of hydrogen for transport and power generation. Japan aims to have 800,000 fuel cell vehicles on the road by 2030, as well as 1,200 buses and 100,000 heavy duty vehicles powered by hydrogen-derived ammonia. Japan has an additional focus on decarbonising aviation fuel and is aiming to replace 10% of aviation fuels with sustainable, hydrogen-derived alternatives by 2030. In the same time frame, Japan is targeting 800,000 tonnes of hydrogen for power generation, to account for 1% of the generation mix.

Similarly to South Korea, our long-term modelling under a net zero scenario, sees Japanese hydrogen and ammonia generation to come online at scale from the late 2030s. In the long term, hydrogen fired units and renewables will act as the marginal generation units in regions across Japan, with regions that rely on hydrogen for a larger portion of generation having higher wholesale prices in general. In both Japan and South Korea, we project ammonia to make up roughly 5% and hydrogen to make up to roughly 25% of the generation mix after 2050.

The Japanese government is focusing its efforts on developing full-scale international supply chains and port, storage and pipeline infrastructure . It has targets for installed capacity of electrolysers with Japanese involvement to increase from 1GW today to 15 GW by the end of the decade, with significant funding expected to be available to first-movers.

Who will win the battle to capture growing hydrogen demand?

The opportunity to leverage demand from East-Asia to develop low carbon hydrogen production is changing the market as 4 countries compete to build out their hydrogen sectors. These are:

- Australia

- Chile

- The US

- The Middle East

Australia is particularly competitive, with low-cost renewable energy, a deep pipeline of low carbon hydrogen projects and partnerships, as well as strong trading relationships and existing export infrastructure. However, the field is far from settled and other countries looking to export can quickly become more competitive in the market as it develops in the period to 2030. Chile and Australia offer the potentially lowest hydrogen production costs thanks to their abundant renewables, while the US and Saudi Arabia may stronger government support and export-ready economies that can take over.

Australia

With its abundant renewable energy resources, land and water and world-leading hydrogen project development pipeline, Australia is well-positioned to become a leading exporter of low carbon hydrogen to South Korea and Japan. Australia can leverage its mature industrial sector and export experience and capabilities to develop low carbon hydrogen projects at scale. Australia’s relationships with South Korea and Japan are particularly strong, with Japan its second largest trading partner and South Korea its third giving a clear advantage in this space.

The Australian government is also providing strong support for the development of the hydrogen industry. The federal government has committed $2 billion to the Hydrogen Headstart program, which will support a small number of large-scale low carbon hydrogen developments. The government is also working to develop a best-in-class certification scheme with the development of the Guarantee of Origin scheme to enable the export of Australian hydrogen products to various jurisdictions with differing requirements. At the state level, there is also strong support for the development of low carbon hydrogen. For example, the Queensland government has committed $62 billion to its Energy and Jobs plan, which includes funding for the development of hydrogen hubs in the state and the New South Wales government has also announced $3 billion incentives to commercialise hydrogen supply chains and significantly reduce the cost of low carbon hydrogen.

To maintain its position as a hydrogen leader in the emerging low carbon hydrogen market, Australia needs to develop pipeline projects beyond early stages, and improve its government support programs and strategy to match global competitors.

Chile

Chile is leading South American hydrogen progress, aiming to capitalise on excellent wind energy in the south and solar in the north to enable international low-cost hydrogen production. Chile is emerging as a global leader in clean energy as renewable developers flock to take advantage of its world class renewable energy resources. Ambitions are extremely high, with Chile expecting to produce the lowest-cost hydrogen in the world by 2030, and to be among the world’s top three hydrogen exporters by 2040. The Government’s National Green Hydrogen Strategy details the roadmap to achieving this goal, including targets of 5GW electrolyser capacity by 2025 and 25GW by 2030. Chile’s potential to become a dominant player in this space is well recognised – with a collection of international and national development finance supporting a $1Bn fund expected to be available from 2024.

The current pipeline for low carbon hydrogen developments is lower in volume than Australia’s and, while material, the $1Bn is lagging funding available in other markets. This is expected to help a small number of first movers, but to achieve its ambitious stated goals, a ramp up in development and investment will be required.

The US

Although the United States has higher LCOEs (levelised cost of electricity) than both Australia and Chile, unrivalled government support for low carbon hydrogen development results in significantly lower LCOHs (levelised cost of hydrogen) for early mover projects. The US has a mature emissions-intensive hydrogen industry, responsible for 15% of the world’s production. However, a substantial percentage of hydrogen production feeds into domestic consumption and is part of an integrated process whereby the producer is also the end user (i.e. in fertilizer production), meaning its production does not translate to export volumes. Japan is already a large importer of hydrogen from the USA, however, partnerships for large-scale low carbon hydrogen exports are not mature.

US government support for the hydrogen industry is currently unmatched, with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) offering a combined over 20 billion USD in funding, stimulating investment interest in clean hydrogen. 17 billion USD from the IRA is allocated to tax credits and funding for direct air capture and hydrogen and sustainable aviation fuels. These credits offer up to 3 USD/kg of low carbon hydrogen for the first 10 years of production for projects with COD before 2033. This will incentivise early investment to capitalise on the credits, but we expect global market distortion caused by this will be limited. This is because the volume of production that can capitalise on this is limited, only sufficient for 5% of current domestic hydrogen consumption over a 10-year period.

For the USA to become a dominant player in the emerging global low carbon hydrogen market, developers need to use government support to build hydrogen production for export, rather than domestic consumption.

The Middle East

The Saudi Arabian government is investing heavily in hydrogen development, looking to leverage its well-developed oil and gas export infrastructure. The country aims to produce four million tonnes of hydrogen per year and to be the world’s leading hydrogen producer by 2030. It plans to achieve this by government investment and subsidies to support the development of both blue (fossil-based production with CCS) and green hydrogen projects. The focus on blue hydrogen development will allow for lower-cost clean hydrogen that will likely satisfy the clean hydrogen requirements in Japan and South Korea in the short term; however, the associated emissions present a risk regarding the emissions intensity requirements of other regions such as the EU, and to changes in emissions intensity thresholds for hydrogen certification.

The volume of potential capital support from the Saudi Arabia government cannot be matched, potentially allowing it to undercut other countries delivered hydrogen costs. Saudia Arabia also boasts the Neom project, one of the few very large scale low carbon hydrogen facilities to have reached financial close globally. Current plans do not leverage the full power of the government, although a greater focus on project development to gain market share of the emerging low carbon hydrogen market would make Saudi exports particularly attractive.

Australia has the lowest unsubsidised delivered hydrogen costs to Japan

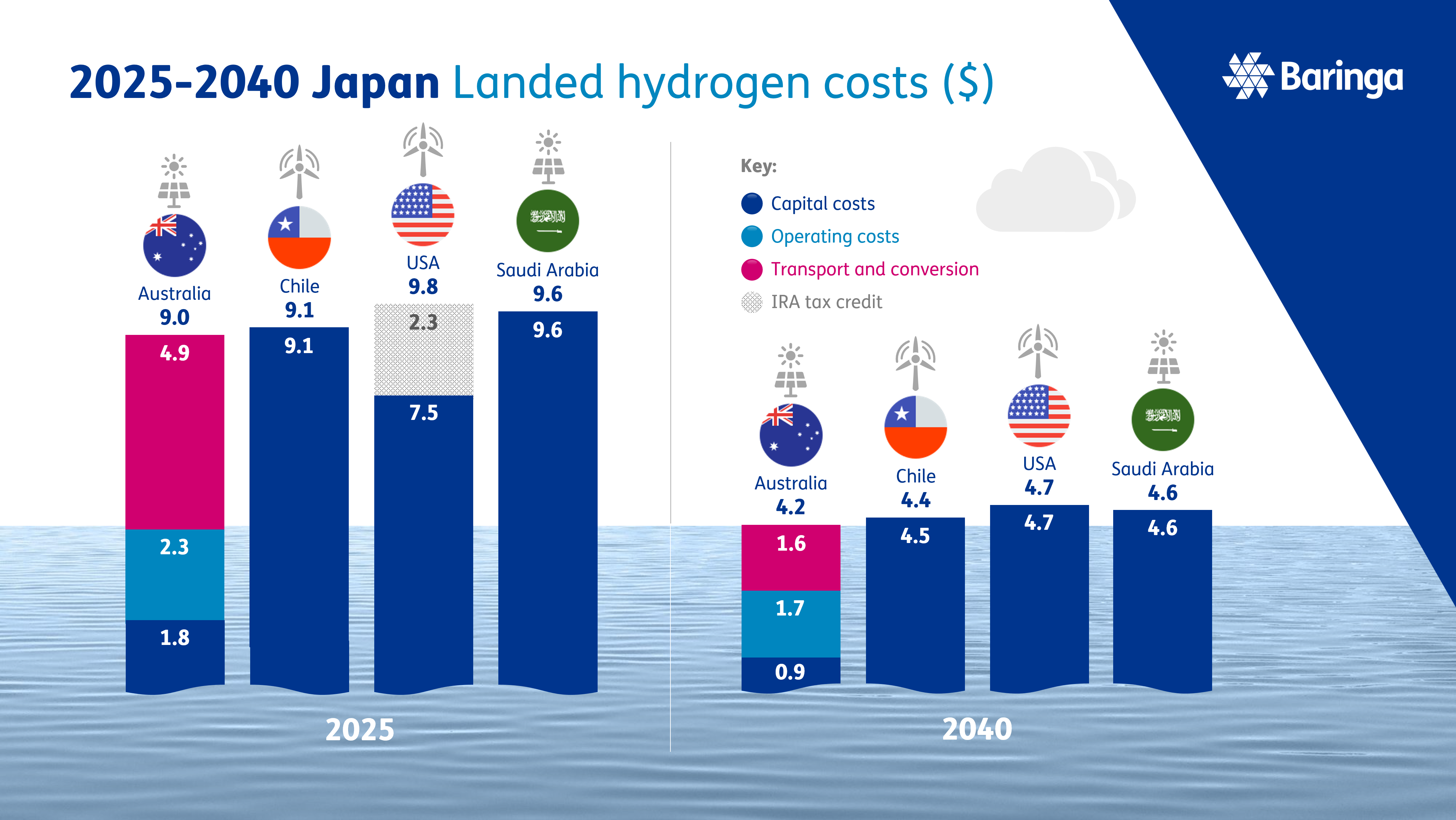

Graph: Landed hydrogen costs (AUD)

This graph shows a comparison of the competitiveness of hydrogen from solar in Queensland, in comparison to low carbon hydrogen exported from Chile, Saudi Arabia and the USA. Export costs compared in the chart below include conversion to ammonia via the Haber Bosch process, ammonia shipping costs, and reconversion via ammonia cracking in Japan. These costs are for a new plant built in 2025 and 2040.

Australia has the lowest delivered costs, driven by the extremely low LCOEs of solar in the north of the country, and supported by shorter shipping across established routes. However, all of these competitors are amongst the lowest levelised costs of hydrogen globally, and the nature of this space as highly dynamic meaning any of them could effectively capture East-Asian demand if they develop through this period effectively.

What should Australian developers do to capitalise on these new opportunities?

Optimise your project for lowest cost hydrogen in a dynamic energy market

Energy costs are responsible for around 70% of hydrogen production costs and optimising this is far from a simple process. Baringa is working with clients in pre-feasibility design to optimally size and utilise generation assets, energy storage, hydrogen storage and firming electricity contracts to minimise production costs. Given the large size of many export projects, their operation, in turn, impacts market dynamics and should be understood as part of the design process.

Realise the need for speed in Exec and Board decision-making to capture first-mover support

Large, long-term investment decisions should not be taken lightly and appropriate diligence should undoubtably be taken. However, we see a clear advantage in being able to demonstrate speed of credible development in terms of subsidy availability for first-movers. Early movers who can take advantage of government support are particularly well positioned for success, while slower developing projects may be less cost competitive without support. Delays of even 6 months may be a difference between eligibility for a subsidy and none. This requires a pro-active approach equipping senior management to understand the risks and economics of projects well ahead of project milestones to avoid having to trade off rigour and speed. We are working with CFOs and management teams across the NEM in this space to distil a complex market into key commercial drivers.

Develop your appetite to manage the market risks associated with buying large volumes of renewable power and selling low carbon hydrogen

Project lifetimes are long and the markets governing input costs (i.e. electricity and green certificate markets) and revenues (hydrogen markets) are in rapid transition. A key differentiation between prospective players in this space is an appetite to accept and build the capability to manage these risks. Flexibility is key in the up-front design of the facility through to operations. Up-front, developers may favour sites with space for behind-the-meter generation, or hydrogen storage, leaving optionality to refine design over the next couple of years. During operations, best-in-class ability to trade and manage the intermittency of renewables in-house, or via partnerships and contracts, is an essential driver of low-cost power.

Collaborate across industries and with local communities

Social license should be a major consideration in any large infrastructure project. This is even more important for first-movers looking to attract government support or the first buyers of hydrogen who will often have stringent requirements given the high-visibility and media focus on these initial projects. Investing in meaningful collaboration with the local community and industry, and being able to quantify the benefits to the broader community should start at an early stage of development. One example of this that we are currently modelling the benefit of flexible electrolysers on the transmission network. We see flexible load as playing an integral part in the network to unlock curtailed renewable generation and provide stability to a deeply decarbonised grid.

The global hydrogen market is emerging and is a fast and dynamic space. Baringa is working end to end across the hydrogen value chain, helping to navigate the uncertainty and capture the opportunities available for developers.

Our Experts

Related Insights

The geopolitics of hydrogen - a new world order

The first installment of our geopolitics in hydrogen report.

Read more

Can green hydrogen produced in the UK be competitive in the emerging global market?

Hydrogen offers a compelling route to market for offshore wind in the UK that would otherwise be grid constrained.

Read more

Texas - the hydrogen export powerhouse of the future

Texas is positioning itself as a global leader in hydrogen exports, which offers transformative opportunities to repurpose existing storage, transport and export infrastructure throughout the state, and in particular on the Gulf Coast.

Read moreIs digital and AI delivering what your business needs?

Digital and AI can solve your toughest challenges and elevate your business performance. But success isn’t always straightforward. Where can you unlock opportunity? And what does it take to set the foundation for lasting success?