Permission to Transition: ESG considerations to achieve net zero

29 April 2022

An estimated $350 trillion globally is required to transition to net zero, but the quantum required to drive us to a truly sustainable world is an order of magnitude greater. While this sum may meet the investment needs to develop low-carbon technologies and energy-efficient retrofits in global infrastructure, it doesn’t include the broader social and environmental requirements to meet net zero sustainably.

As the latest IPCC report makes clear: future climate change and ecosystem health is determined by ‘human systems transition’, involving both technological and societal shifts to achieve ‘human health and well-being, equity and justice’.

To meet net zero, permission is needed from society. The energy transition is not occurring in a silo, but within a system of workers, households, and decision-makers who each stand to benefit from the shift to renewables. In the current pathway to net zero however, not everyone is benefitting: reducing emissions can sometimes cost people’s livelihoods and ecosystem health, as explored in this article. In practice, meeting net zero therefore requires permission in the form of people’s buy-in to enact behaviour change and their trust that transitioning to low-carbon technologies will leave no-one behind. In ESG terms, this means that we will not meet net zero unless improving livelihoods under “S” and ecosystem health under “E” is properly accounted for.

Fundamentally, the IPCC places finance as central to achieving this. Historically, governments and development banks have borne the costs of environmental and social investment. However, the growth of green finance and ESG - with more than $1 trillion invested in ESG in the last two years - shows there is economic value for private finance in sustainability. For example, companies with higher ESG scores performed 50% better than their peers during the pandemic. ESG brings new risks to the financial sector on one hand, but enormous opportunity to access sustainable value on the other. Although finance has begun incorporating climate change into investment, lending and underwriting decisions, the greater challenge lies next: making financial decisions which simultaneously drive positive social and environmental outcomes.

The fundamental starting point is understanding how net zero and ESG are intrinsically linked…

The link between net zero and ESG

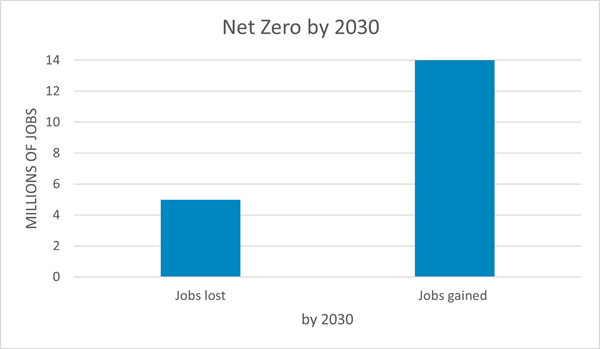

The energy transition is creating new jobs in clean energy. But at the same time, the labour market impact on workers in high-carbon sectors is stark. Forward-looking projections of potential disruption includes the IEA’s most recent outlook which reports that 5 million jobs may be lost, while simultaneously 14 million jobs will be created by 2030 under existing pledges. Real-world examples, however, show us that the trade-off between the energy transition and improving livelihoods is already unfolding on a global scale.

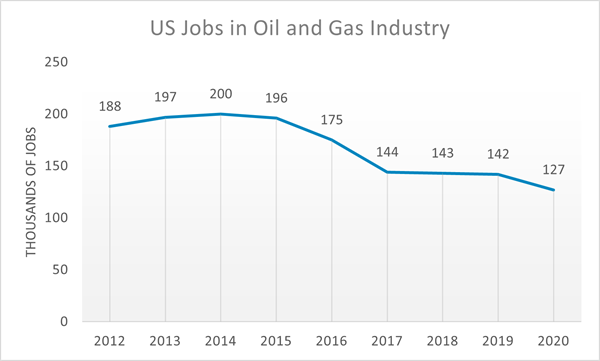

Ensuring that net zero does not leave behind communities who are dependent on fossil fuel extraction has become a priority for the Biden Administration alongside its crackdown on coal, oil, and gas. US oil & gas employment fell to a multi-decade low in 2020, while coal mining employment dropped to 46,600 in 2020 from 90,000 in 2012. Concerned about job security and wages in the clean energy sector, coal miners are also successfully lobbying to stall the legislation of Biden’s climate agenda and, in doing so, the decarbonisation of the US economy. This shows a boomerang effect in ESG risk, whereby the negative social impact of net zero solutions can ultimately hinder environmental progress, unless a comprehensive view of ESG risks and other mitigating levers is taken from the outset.

In lower-income countries, the impact of net zero on livelihoods is compounded with more extreme social issues. South Africa’s economy faces an enormous labour market shift if it is to decarbonise, with 88% of its energy generation in 2019, 73% of its energy supply in 2018 and 1% of total formal employment derived from coal. Against a backdrop of long-term unemployment and inequality, displaced coal workers are unlikely to find new jobs as easily as their US counterparts. Australia’s rural coal workers, despite living in a high-income country, similarly possess a weaker union voice and lower levels of statutory support in the face of plant closures.

Elsewhere, nature-based solutions provide an example of creating long-term mutual benefits for communities, the climate and biodiversity. These will only be successful if they are science-based mechanisms which reduce emissions, sustain or increase ecosystem function and gain agreement and participation from local communities. However, some net zero solutions such as lithium mining support the rising demand for zero and low-emission vehicles but fail to meet combined ecosystem and development objectives and, in turn, face increased social risk.

Net zero solutions will fail unless the welfare of all stakeholders affected is accounted for. The real-world trade-offs between environmental solutions and improved livelihoods show that delivering a Just Transition – ensuring the benefits of the economy’s green transition are shared among all stakeholders globally - is a question of synergies and obtaining the greatest improvement in social opportunities and welfare per unit of carbon. This is especially the case in low-income regions and developing countries.

|

Snapshot: Social Risks in Lithium Supply Chains The IEA estimates that EV sales are expected to jump from 3 million in 2017 to 23 million by 2030. While this will contribute to crucial reductions in transport emissions, the wider social and environmental costs are stark. Farming communities in Argentina, Bolivia and Chile – where over half of the world’s lithium resources are found – are losing vital access to water in an increasingly dry climate. Driven by concerns among local communities Chilean lawmakers filed objections to 29-year lithium mining contract bids in January. Chile’s Christian Democrat Party have also introduced a bill to prevent outgoing presidents’ invitations for new mining contracts. If passed, these political and civil society efforts represent increased social risk to investments in lithium mining projects in Chile and beyond. |

What does this understanding of ESG mean for financial decision-makers and how can you effectively embed ESG into investment, lending and underwriting decisions?

Making balanced ESG decisions

The permission from society needed to achieve the net zero transition has enormous implications for how ESG is practiced in finance. To maximise the shared value from each decision in your organisation, you need to have a balanced and comprehensive understanding of their environmental and social impacts.

Here are four key factors for making robust ESG decisions:

- Consider the social and environmental impact of climate decisions. Given the linkages and trade-offs between E, S and G factors, a siloed approach to ESG will ultimately fail to create the value that matters to society and the organisation. To what extent are you scoping your boundaries of social and environmental impact at a local and global level? And crucially, how will you best work with clients to ensure they do the same?

- Measure and monitor social impacts. Sound ESG data is difficult to source and ESG ratings don’t tell you the whole story. To make robust ESG decisions, an expanded data infrastructure is needed along with collecting the best ESG data available while the landscape develops.

- Communicate your approach to stakeholders, credibly. Disclosure is pivotal to gain buy-in from society. Today’s high-pressure scrutiny on financial institutions’ ESG outcomes shows the importance of not only meeting reporting requirements, but an opportunity to build credibility through being transparent about your real-world impact.

- Align your corporate purpose to sustainable outcomes. Any strategy should be built around a clear view as to how your organisation interacts with and adds value to society. Your ESG outcomes are the necessary outcomes of this. This calls for your purpose to be defined and communicated across the organisation, which requires open conversations, strong ESG capabilities and purpose-led leadership to drive transformation.

Part of the system, driver of the solution

Taking these four considerations into account will help drive your organisation towards making sustainable decisions and investments. The economic value of doing so stretches beyond branding and reputational benefits. Making robust ESG decisions contributes to the proper management of ESG risks and accessing economic activities which generate value based on sustainable outcomes and resilience. As a result, banks stand to benefit from increased creditworthiness among ESG-aligned clients, while investment managers are already seeing ESG-aligned funds outperform standard portfolios.

Now that ESG is here to stay, the risk of not being part of the solution only continues to grow. Finance faces an unlimited opportunity to create shared value for shareholders, employees, the planet and society.

How just are your net zero decisions?

To find out more about how we can help you, please contact us.

Our Experts

Related Insights

Future-proofing climate disclosures: Leveraging climate reporting for nature

Forward-thinking companies are integrating climate and nature into their strategies to drive innovation and resilience.

Read more

Transition planning in turbulent times: How financial institutions can adapt and lead

The shift to a low-carbon economy is challenging for financial institutions; we explore how they can adapt and lead in today's tough landscape.

Read more

Simplification Omnibus: what you need to know and where to go from here

We share what the Simplification Omnibus means for CSRD, CS3D and the EU Taxonomy and how you should respond.

Read more

2025 Outlook: What lies ahead for climate and sustainability in financial services?

Here's what's front of our minds for 2025 based on our dialogue with, and work for, climate and sustainability leaders across financial institutions.

Read moreIs digital and AI delivering what your business needs?

Digital and AI can solve your toughest challenges and elevate your business performance. But success isn’t always straightforward. Where can you unlock opportunity? And what does it take to set the foundation for lasting success?