Millions at risk of financial vulnerability

11 February 2022

Living standards ‘crunch' set to stoke financial vulnerability

A series of negative compounding factors threatens a cost-of-living crisis for UK households. This could have wide-ranging implications for financial vulnerability and corporate credit risk.

This is the first of a series of articles shining a light on financial vulnerability. We dive into this topic to explore how inflation threatens living standards and interest rate trade-offs will hit the poor hardest.

Covid measures have caused long-term structural damage to the UK economy, and this is starting to be felt across the country.

The average UK family faces a £2,000 hike in annual bills – enough to force millions into a vulnerable financial position. Rising inflation (driven by energy costs) and interest rates will hit lower-income households hardest. At the same time, many businesses are themselves indebted and face a difficult trading environment with potentially spiralling costs. Businesses must be taking steps to identify newly vulnerable customer groups, to uphold their regulatory and societal obligations, while ensuring they are best positioned for this new economic context.

There has been a welcome rebound in economic activity since the end of lockdowns, but it is now clear that the UK economy will be structurally damaged. The economy is thought to have returned to pre-crisis levels of GDP, but what has been forgone by way of economic activity will not be recouped. The trend rate of growth has been permanently altered.

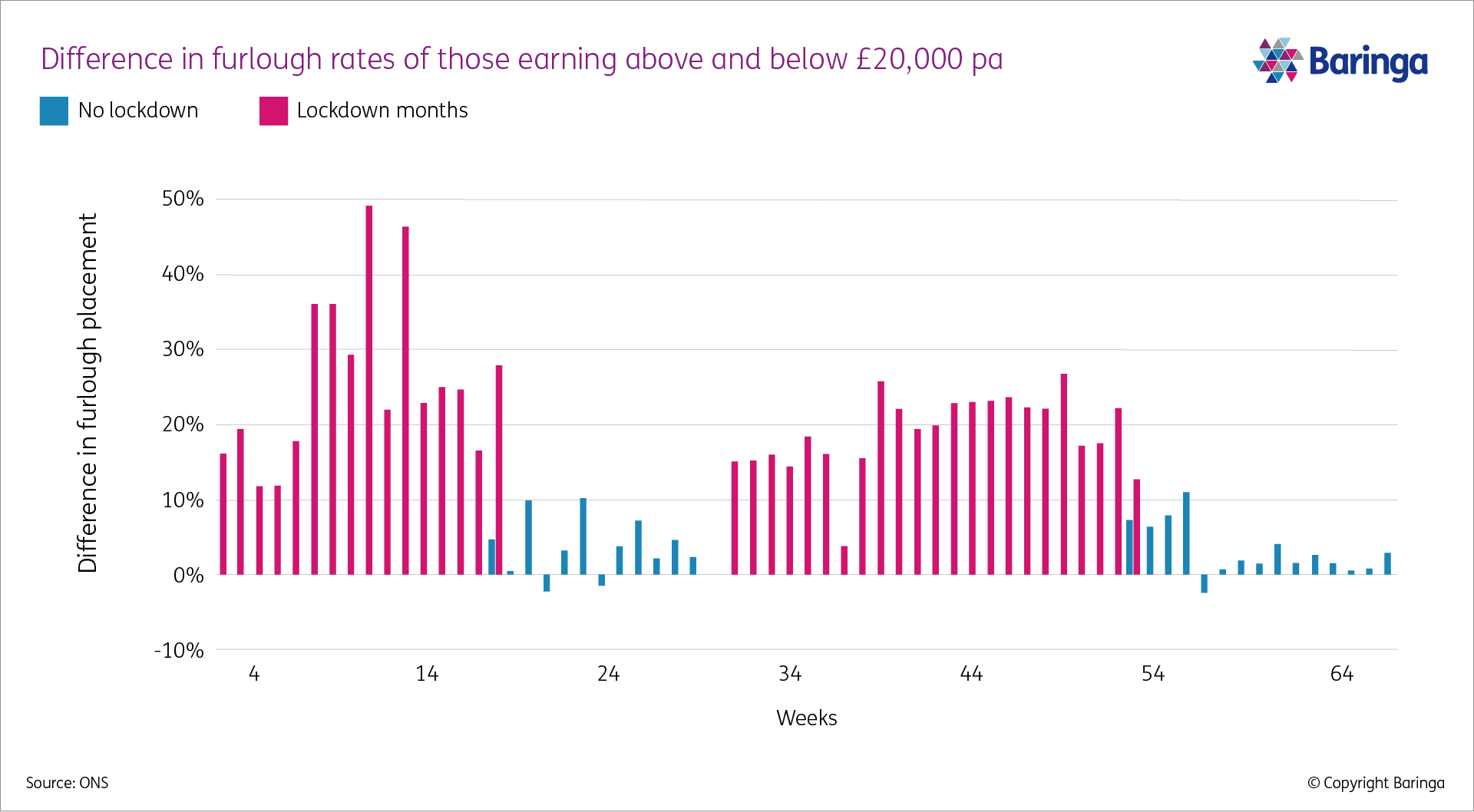

The consequences of this have been born out in the labour market. While the furlough scheme insulated workers from the full force of the government restrictions on economic activity, the effects were not evenly distributed.

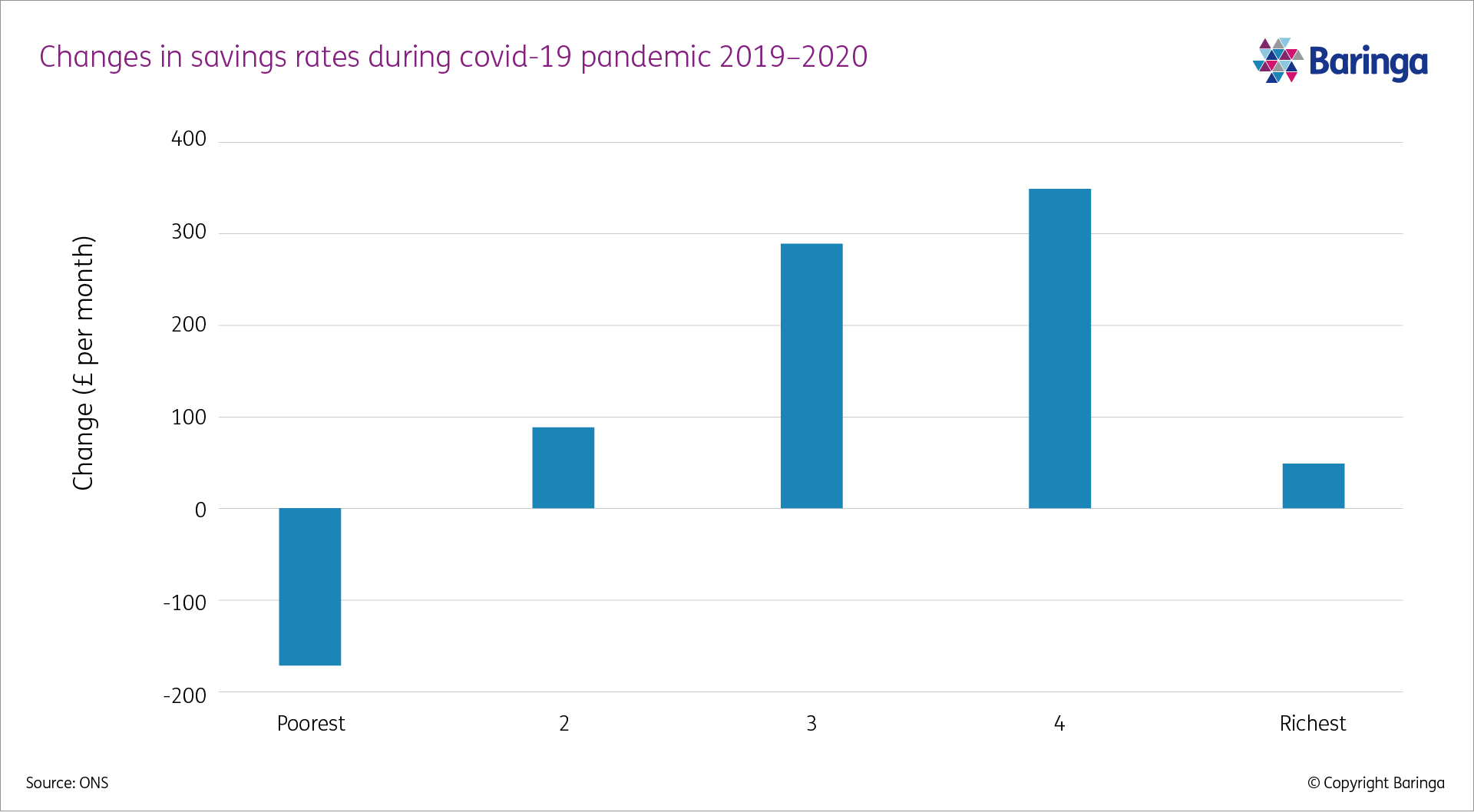

Figure 1 shows that lower-income groups were up to 50% more likely to be furloughed during lockdown months, and as a consequence were the most likely to report lost income and depleted savings (Figure 2). Similarly, while 90% of furloughed workers have since returned to work, or found other employment, the remaining 10% are disproportionately found in lower-income groups. Young people, in particular, were more affected, owing to their high prevalence in hospitality and retail sectors.

This creates a vulnerable macro–context with signs of distress already elevated for certain groups.

Figure 1

Figure 2

It is within this fragile context that the economy now faces two other compounding challenges, amounting to a “cost of living crisis.” The first of these is inflationary pressures.

Inflation threatens living standards

Rising inflationary pressure threatens to undermine the wage recovery seen in recent months, and to compound a cost-of-living crisis for vulnerable groups.

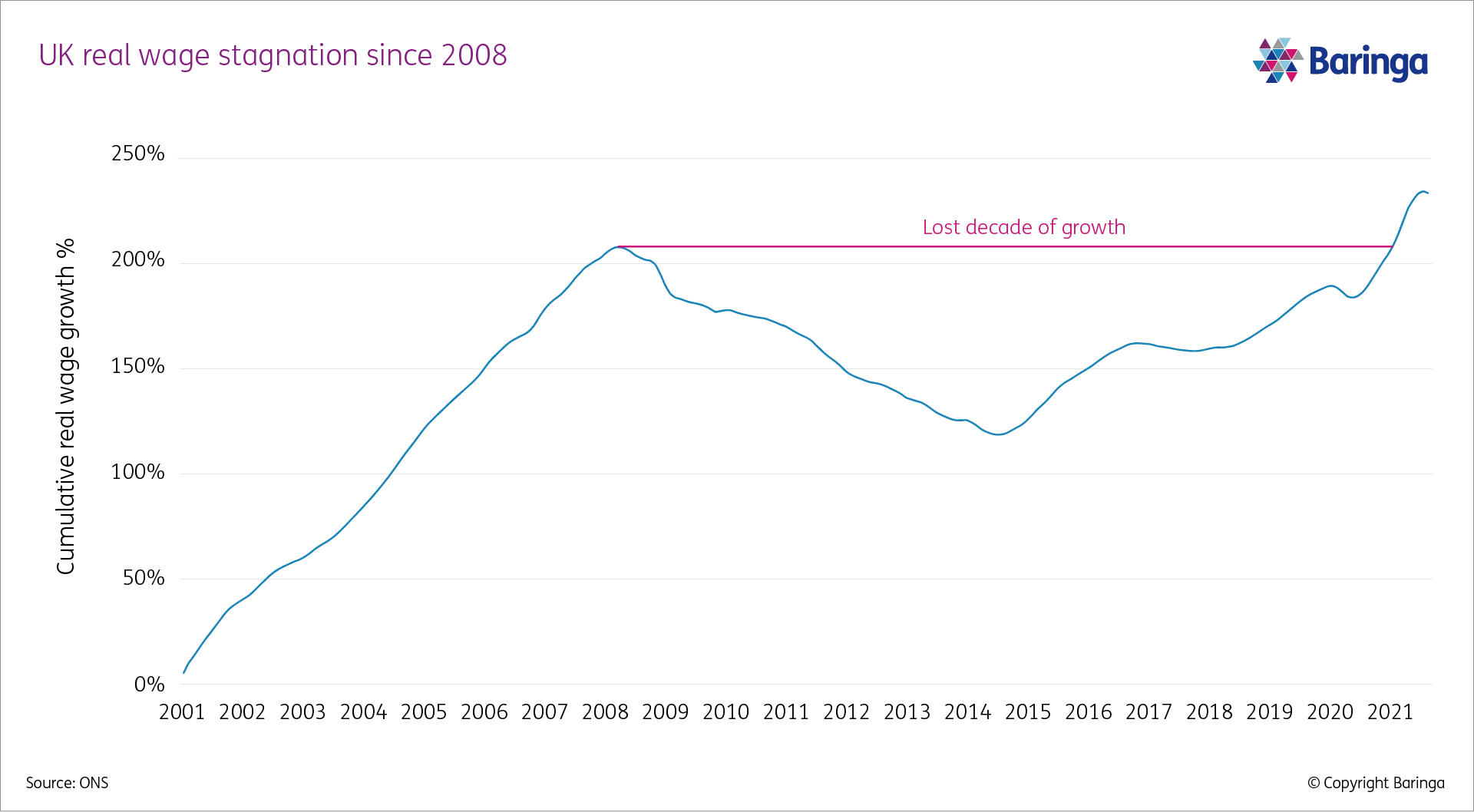

The long shadow of 2008 has had painful implications for UK wages. The UK has experienced a “lost decade” of real wage growth, as productivity collapsed after the global financial crisis (see Fig. 3). Wages remained below 2007 levels right up until 2020. The major contributors to GDP growth since 2008 have been a combination of a larger workforce and rising asset values as opposed to productivity growth; ultimately hindering wage growth for UK households.

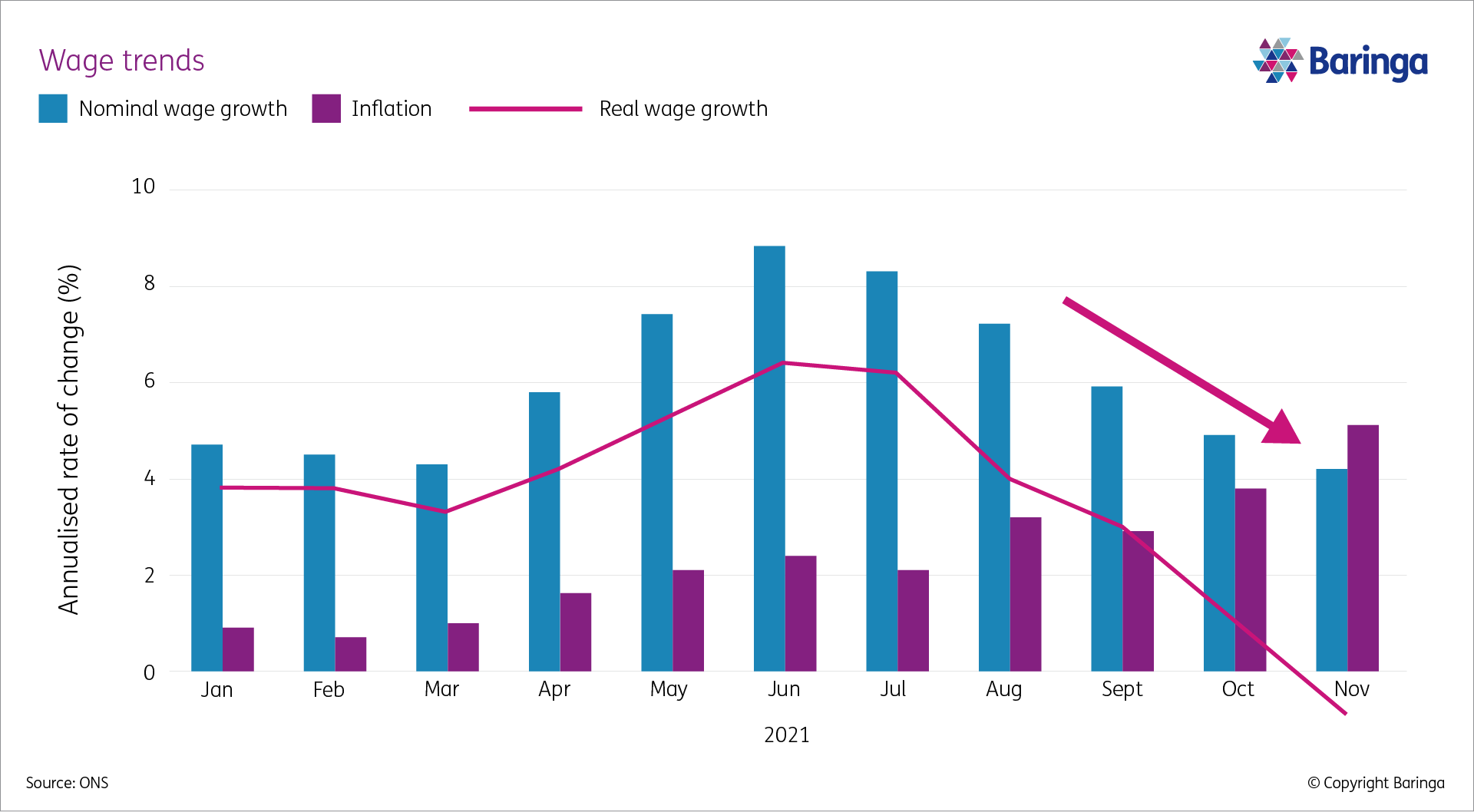

Initially, economists looked positively on rising nominal wages as pent-up demand, supply shortages and new labour mobility restrictions created rapid nominal wage growth in the first three-quarters of 2021.

However, rising inflationary pressures have reduced the real impact of those wage rises. Fig. 4 shows real wage growth was running at about 5% in June 2021 on an annualised basis but rising inflation has cooled hopes of an end to the recent years of wage stagnation, with real wage growth falling back to a meagre 1% or so in October and turning negative in November.

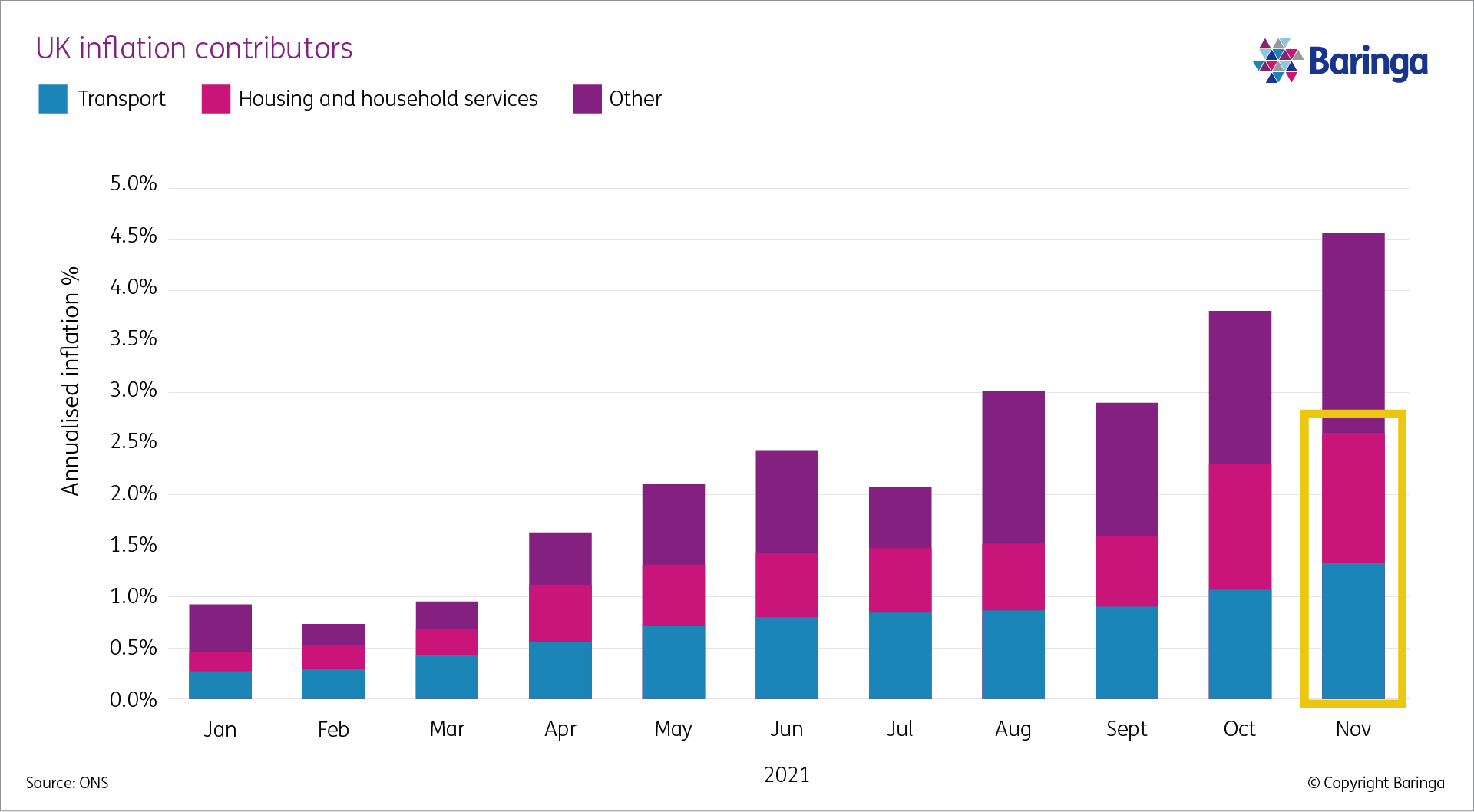

The expenditures most exposed to inflation constitute a greater proportion of outgoings for financially vulnerable groups. Collectively, energy-related inflation (as defined by housing expenses and transport) have contributed about 50% to rising inflation in recent months, as shortages in wholesale markets drive an energy supply shock (see Fig. 5). With lower income households spending proportionally more on these categories (up to 40% of their disposable income relative to 20% for the average household) this inflation spike is very likely to hit the poorest hardest.

These inflationary pressures are only expected to worsen in March 2022, as the energy price cap is reviewed, and the full impact of the European wholesale gas shortages are incorporated into retail prices for UK households. Announced recently was a rise in the cap of 50%, with a further rise expected in October 2022.

Disposable incomes are expected to be squeezed materially in the new year, with those groups that have already been hit the hardest, affected most.

Interest rate trade-off will hit the poor

For a time, demand and supply pressures were expected to drive a “transitory” shot of inflation as the mothballed economy roared back to life. But there are growing fears that inflationary pressures may be more permanent.

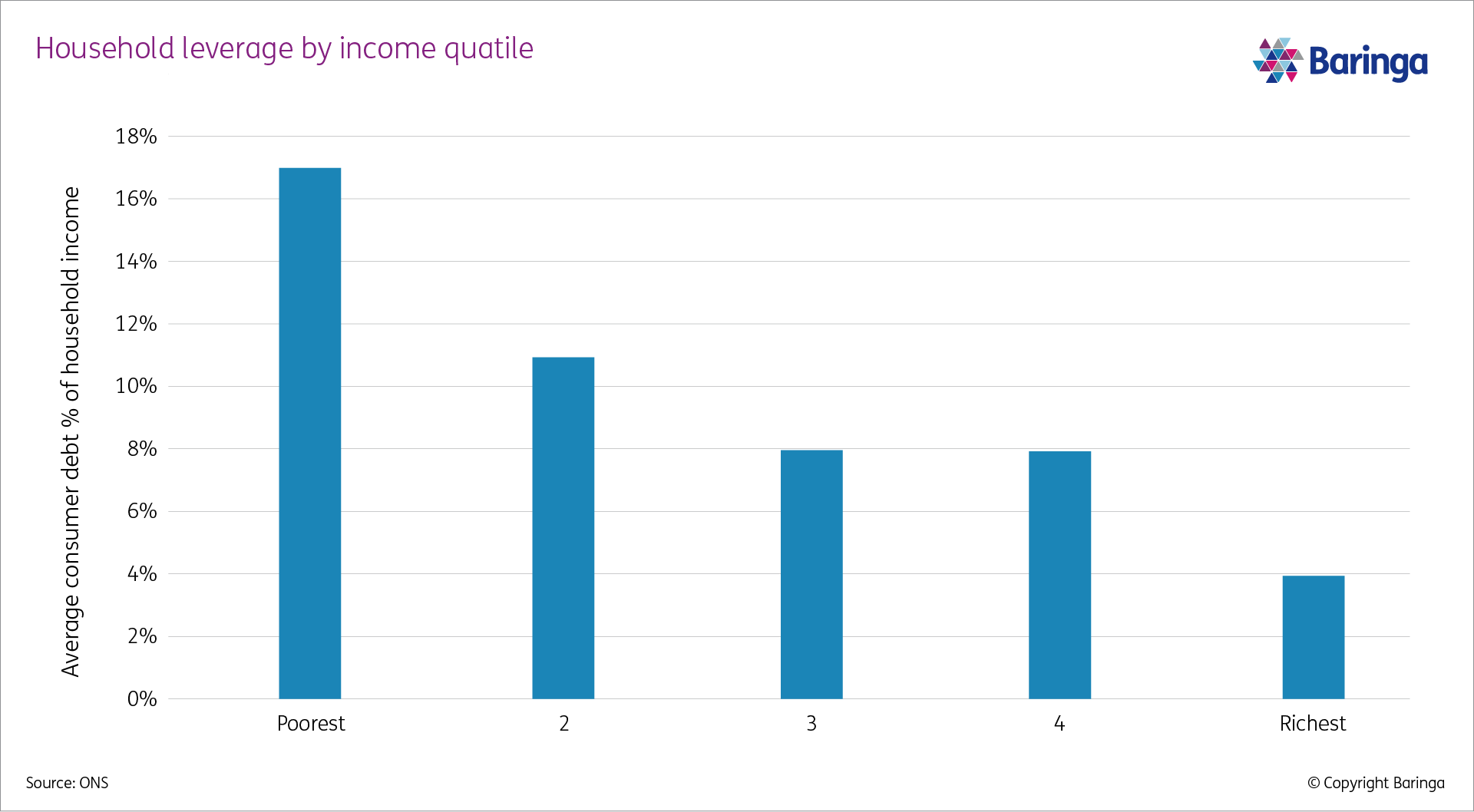

Central banks, which were initially concerned that interest rate rises could destabilise a fragile recovery, have started to act, with a 0.15% rise by the Bank of England in December and a further 0.25% rise in February. While the move was seen as necessary to maintain economic stability, it comes with a sting. Exposure to variable interest rates is highest among the poorest. Worse still, household leverage, a measure of debt-over-household-income is considerably higher in the bottom decile, making debt sustainability of particular concern amid a rapidly rising rate environment (see Fig. 6).

Housing costs are expected to be hit with variable ratepayers seeing average mortgage costs rise by £115 from this 0.15% rise. A 0.5% rate rise, returning us to the base rate of Jan 2020, would increase the cost of mortgage repayments by an average of £500 per year.

On top of this, the introduction of tax and spend changes in March 2022 will reduce disposable incomes further. Universal credit reductions and national insurance tax rises threaten take-home pay, just as the macro-headwinds for vulnerable groups worsen.

Businesses that weather the storm and help the economy grow through it, will be proactively adapting their strategies to more support financially vulnerable customers as the risks facing them mount up. By embracing a customer-led approach, underpinned by data and technology, the corporate sector can shore up its own financial robustness, while becoming a tremendously positive force in the wider economy.

In our next article on Financial Vulnerability, we will look in more detail at how the economic context is affecting different groups, business sectors, and regions.

Get in touch with our experts

Caspian Conran, Political economics

Vlad Parail, Political economics

Related Insights

Navigating financial vulnerability across the UK

We explore the underlying causes of financial vulnerability and examine the outlook for winter 2025.

Read more

Britain’s poorest face doubling of debt to energy suppliers

According to Baringa's figures, Britain’s poorest people now owe twice as much to energy suppliers as they did during the 2022 energy crisis.

Read more

Taking a person-centred approach to managing financial vulnerability

As Australia starts to feel the impact of rising energy bills, we share our view.

Read more

Safeguarding Financial Vulnerability

Growing numbers of customers, and businesses, are more financially vulnerable than ever.

Read moreIs digital and AI delivering what your business needs?

Digital and AI can solve your toughest challenges and elevate your business performance. But success isn’t always straightforward. Where can you unlock opportunity? And what does it take to set the foundation for lasting success?