What are the biggest challenges for oil and gas going forward?

26 April 2022

The agreements made at COP26 at the end of 2021 will directly affect the climate for generations to come – and the future of oil and gas. As demand for fossil fuels drops, oil and gas companies have some difficult choices to make.

In one scenario exercise, Baringa’s analysis suggested that, based on current business models, only a third of Tier 1 oil and gas companies would survive the projected changes to the energy market. So, businesses need to act now to prepare for the bumpy road ahead.

In this series of blogs, we share our insights on how climate change and the response to it will affect the oil and gas industry. And we’ll recommend how companies can analyse their risks, cut their operational emissions, and create low-carbon businesses so they can thrive through the energy transition.

Price drops, lawsuits, and tension with talent: The future of oil and gas

In 2021, for the first time, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded that burning coal, oil, and gas directly causes climate change. They warn that unless emissions are drastically reduced immediately, it’ll be impossible to limit warming to 1.5°C. Deal with a tricky energy transition now, or accept a spiralling climate later. That’s the choice we face.

So where does that leave oil and gas companies? The physical risks from a changing climate are already threatening safe operations – and denting bottom lines. But as governments step up to the IPCC’s words, there are more challenges to come – regulatory, financial, legal, HR.

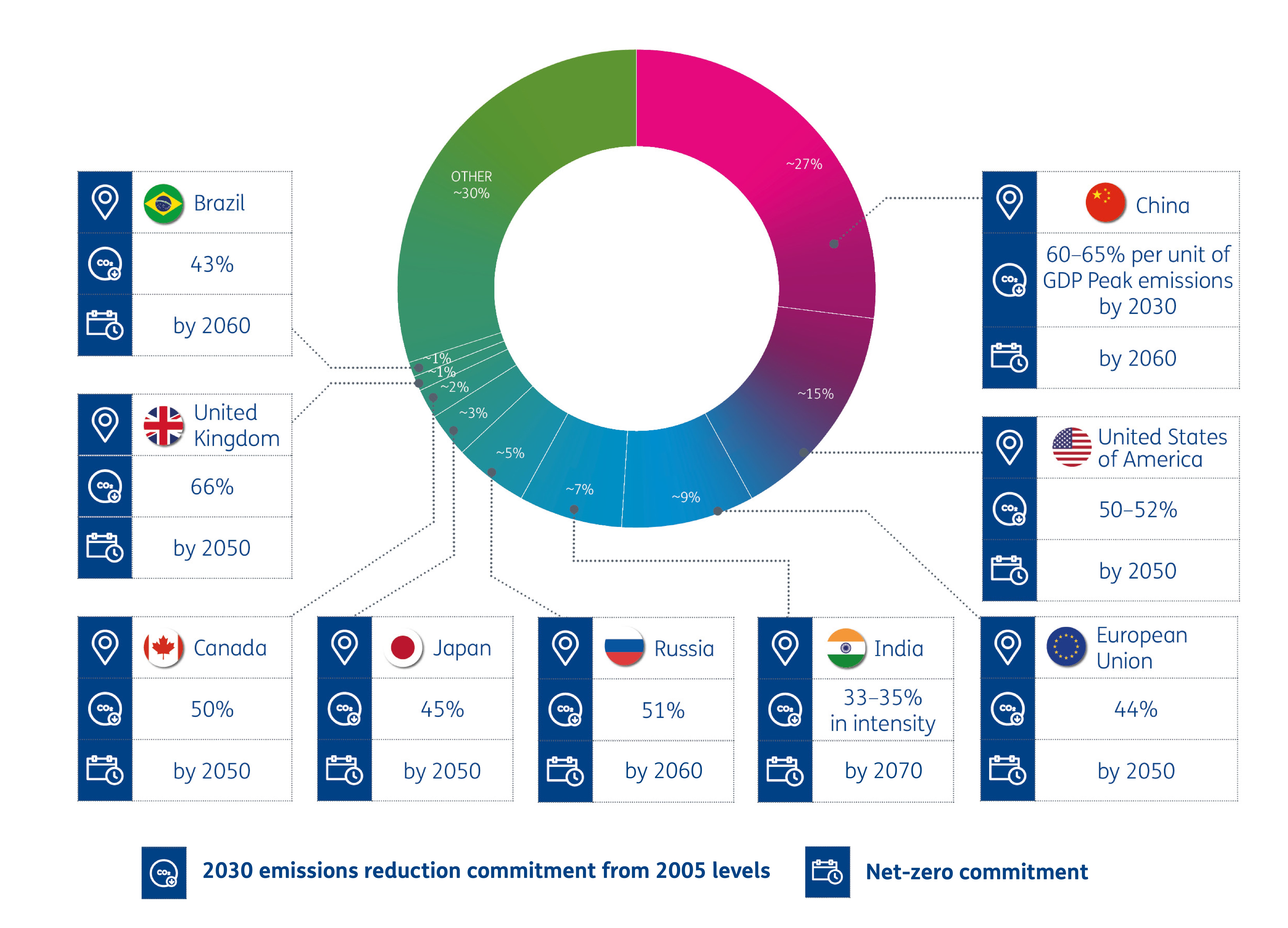

Regulatory implications: Governments are likely to increase national commitments

To spare the world from the worst impacts of climate change, the goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement was to limit global warming to 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels. More than 125 countries committed to peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, and a climate-neutral world by mid-century.

But current commitments are still leading us on a path to warming of 2.7oC or more by 2100. So, governments are under pressure to increase their national defined contributions (NDCs) at COP27 in Egypt later this year.

Fig. 1: National defined contributions of countries with >1% of global emissions.

To realise their emissions reductions commitments, governments are targeting the power and transportation sectors, responsible for a significant share of emissions. Most of the world’s top countries by GDP have proposed bans on petrol and diesel vehicles. In response, the largest manufacturers have already announced they’ll stop making fossil-fuelled vehicles. On the supply side, 64 governments worldwide have introduced carbon taxes or similar measures aimed at reducing emissions. Regulations designed to steer companies away from fossil fuels are only going to increase.

To realise their emissions reductions commitments, governments are targeting the power and transportation sectors, responsible for a significant share of emissions. Most of the world’s top countries by GDP have proposed bans on petrol and diesel vehicles. In response, the largest manufacturers have already announced they’ll stop making fossil-fuelled vehicles. On the supply side, 64 governments worldwide have introduced carbon taxes or similar measures aimed at reducing emissions. Regulations designed to steer companies away from fossil fuels are only going to increase.

Financial implications: The cost of capital will rise for companies that aren’t Paris-aligned

The risks from climate change and the financial instability it might lead to are ringing alarm bells in the global financial services sector.

Banks, insurers, and asset managers are starting to measure their counterparties’ credit quality under different 2-degree transition scenarios. In a recent Bank of England scenario analysis exercise, by 2050, oil and gas demand fell by as much as 60% and 75% respectively, and the price of oil fell to $33/boe and of gas to almost zero. Meanwhile, the carbon price rose to $900 per tonne in the UK and EU.

Baringa supported more than half of the 18 participants in this exercise. We concluded that, based on current business models, only 30% of Tier 1 oil and gas companies would weather such drastic changes.

Shareholders are also demanding that banks, insurers, and asset managers set net-zero targets for their lending and investment portfolios, including counterparties’ Scope 3 emissions. Scope 3 includes emissions from customer combustion of sold products, which for oil and gas companies is typically ~90% of their total emissions. Oil and gas companies thus risk falling outside lenders’ and investors’ net-zero commitments and becoming unable to raise the finance they need.

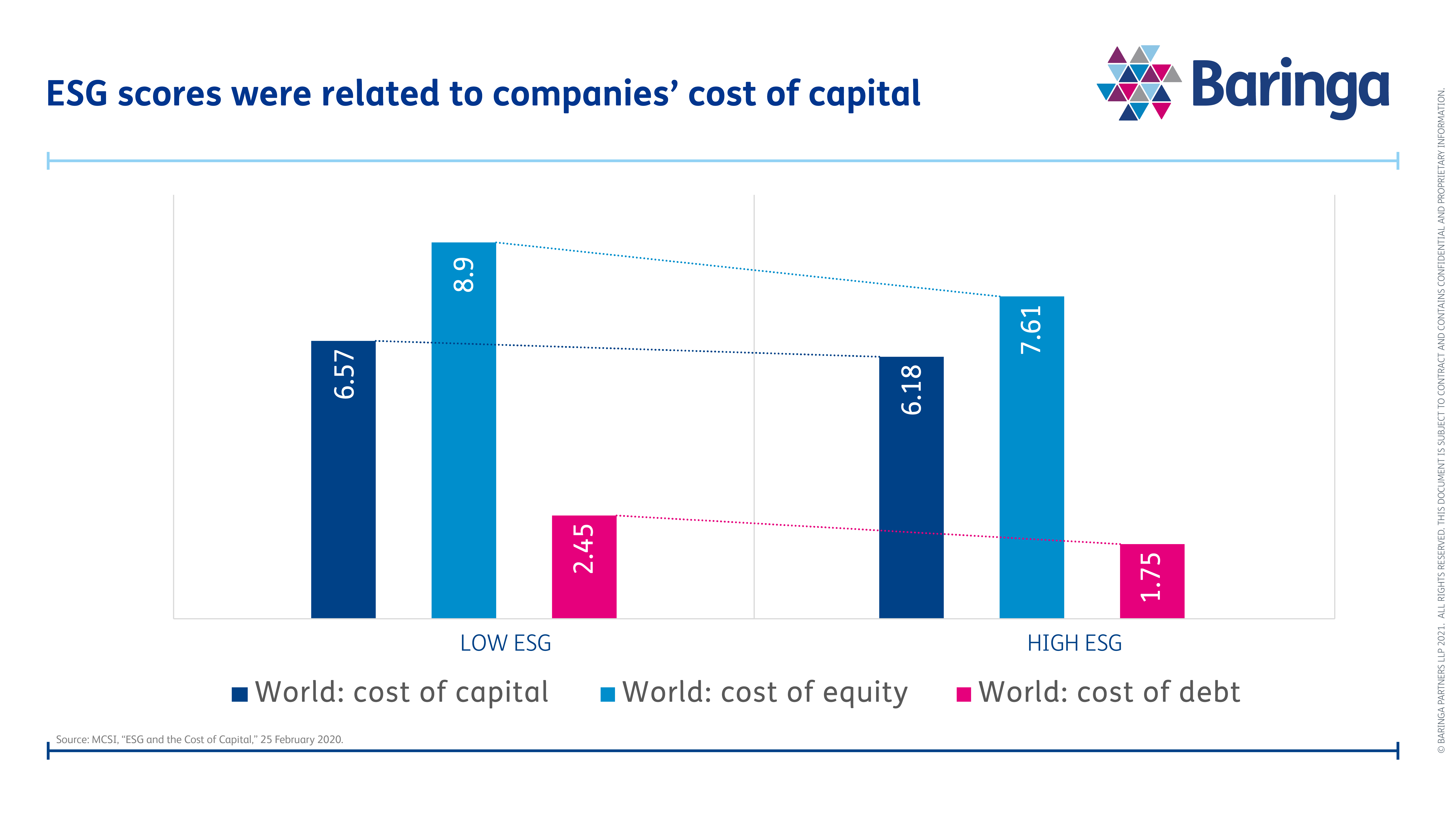

Investors are moving their money into sustainable funds, with 2020 seeing a 96% increase of such investments from 2019. This means the cost of capital, equity, and debt is lower for Paris-aligned companies, and higher for those who are not.

Fig. 2: ESG scores related to cost of capital, equity, and debt

Legal implications: More lawsuits will target oil and gas companies

As societies increasingly take a dim view of producers and consumers of coal, oil, and gas, we expect more litigation against companies not aligned to Paris goals. Over the past two decades, climate lawsuits in 52 countries have tried to change government policy or claim compensation from fossil fuel companies for their contributions to global heating.

Staffing implications: Oil and gas companies may struggle to attract talent

In recent polls in the countries with the highest emissions from the power sector, majorities supported renewable energy and clean vehicles. In a survey of 1,200 young Americans, 62% say a career in oil and gas is unappealing. Two out of three believe the oil and gas industry causes problems rather than solves them. Such unfavourable opinions will make recruitment difficult going forward.

The oil and gas industry is under growing pressure to address climate change issues, with many companies struggling to understand the implications to their business and plan for the future. Join us next time as we explore how oil and gas companies can begin developing their long-term strategies by assessing their climate risks.

For more information contact us.

Related Insights

Dissecting the REMA decision

Three years in the making, the Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA) decision has now been published: the UK Government has decided to retain the national wholesale price.

Read more

What might a reformed GB national power market look like under REMA?

Discover how a reformed national market is likely to include significant changes to current market arrangements, with material impacts for market participants.

Read more

Investing in uncertainty: European power market outlook 2025

Our latest outlook points to a more uncertain energy transition, shaped by political and economic volatility across Europe in the form of Trade Wars, Populism and Remilitarisation.

Read more

REMA and investing in GB power market under uncertainty

Learn about the opportunities and challenges of investing in the GB power market under uncertainty and how Baringa can help

Read moreIs digital and AI delivering what your business needs?

Digital and AI can solve your toughest challenges and elevate your business performance. But success isn’t always straightforward. Where can you unlock opportunity? And what does it take to set the foundation for lasting success?