It's time for finance to turn its efforts to the biodiversity crisis

1 September 2022

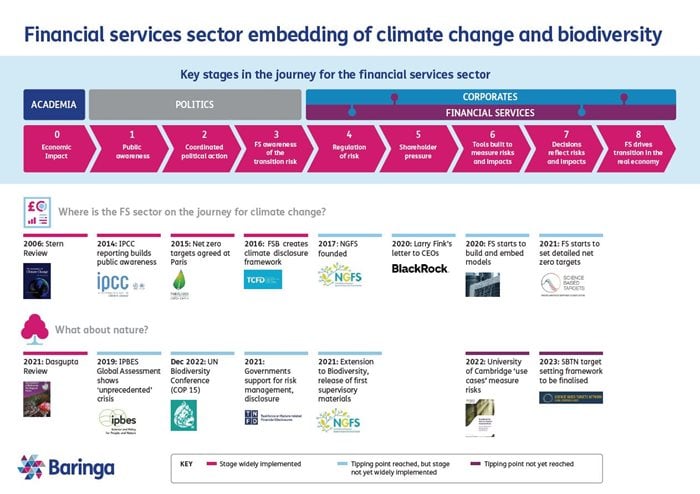

The past five years have seen an extraordinary effort on climate change across the financial sector – an effort that is still not complete as we strive to create a financial system which is resilient to climate risks and supports the scale of capital flows, and which enable the transition to net zero.

As much as that is an ongoing effort, it’s time for finance to turn its efforts to the biodiversity crisis. Here are some thoughts on why, and how.

Climate and biodiversity are interconnected – the intergovernmental body IPBES estimates that climate is responsible for 16% of biodiversity loss, however, nature-based solutions are also expected to provide over a third of anticipated emissions mitigation between now and 2030. This interconnection is underscored by the recent finding that wildfires have eradicated 95% of the carbon offsets in California's forest carbon trading system.

Click to Enlarge

In responding, we must start by considering what aspects of climate risk capabilities can be used, or augmented, in responding to biodiversity - such as physical climate risk scenarios for wildfires or droughts.

We should also consider the existing mechanisms within financial services which address biodiversity – for example, sector policies and screening in sensitive sectors, such as forestry or agriculture, and nascent efforts within financial crime teams to build indicators to identify financial flows linked to wildlife crime, like that of the United for Wildlife Financial Taskforce.

But these efforts alone risk missing the transformation that has already taken place in the thinking on climate, and that now needs to occur on biodiversity. As recognised by central banks and regulators within the Network for Greening the Financial System, biodiversity is a potential source of systemic risks which are not currently being measured and priced within financial institutions.

Just as important, the agreement in December 2022 of a post-2020 biodiversity framework, via the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), will help support capital flows toward what is a significant investment opportunity, with suggestions that the financing gap is between $600-800 billion a year. The draft CBD proposal is to close that gap through targeting a blend of $200 billion a year in new financial flows by 2030, coupled with $500 billion a year in incentive reform.

There is much we don't know – many competing and overlapping terms; biodiversity, natural capital, ecosystem services – and much discussion on what metrics are appropriate to measure risks, impact and dependencies. We don't, and shouldn't, enjoy the simplicity of a single CO2 equivalent for nature, as it is not fungible but instead locational and multidimensional. This requires a more sophisticated approach to metrics, selected with care, to reflect business model and impact.

There is also the reality that, like the difference between scopes of emissions, nature-related risks flow through value chains and between sectors. Like the initial focus on fossil fuels when considering climate response, it’s easy to argue that early efforts should focus on forestry and agriculture as those responsible for the primary biodiversity impact. But risks will show up elsewhere in sectors as diverse as healthcare or consumer goods. Where to look for these will depend on the business model and strategy of each financial institution. At heart, more than half of global GDP is moderately or highly dependent on nature.

This brings us to the critical work of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, or TNFD. Imitation being the sincerest form of flattery, TNFD echoes not only the name of the TCFD but adopts it's four pillars and eleven recommended disclosures, while adding a twelfth: an organisations’ interactions with ‘low integrity’ ecosystems, those of high importance or facing water stress, to reflect the critical role of location in managing these risks. TNFD has also learned from TCFD, and as a result, is going through a series of pilot phases until 2023, focussing on ensuring it has a viable risk management framework to enable firms to disclose information.

The path ahead of us will be hard – financial institutions are already part-way along that path thanks to their efforts on climate, but they are also tired from that exertion. And the questions ahead are big: How large are the nature-related financial risks and where in financial portfolios are these found? How large are the opportunities emerging from biodiversity protection and restoration? And how large are a financial institutions’ impacts on nature arising from financing activities?

In response, financial institutions should now be monitoring, and considering participation in the TNFD consultation, thinking about the questions it raises, such as what sectors and geographies they allocate capital to, how their asset classes and financial products interactions occur with nature, and what ecosystems these give exposure to. Underlying this are questions of ambition and intent. Some may respond by capturing opportunities, some by managing risks – but those who start preparations now will make faster and easier progress down the path.

Want to know more about how to respond to the biodiversity crisis? Contact Simon Connell.

Related Insights

Future-proofing climate disclosures: Leveraging climate reporting for nature

Forward-thinking companies are integrating climate and nature into their strategies to drive innovation and resilience.

Read more

Transition planning in turbulent times: How financial institutions can adapt and lead

The shift to a low-carbon economy is challenging for financial institutions; we explore how they can adapt and lead in today's tough landscape.

Read more

Simplification Omnibus: what you need to know and where to go from here

We share what the Simplification Omnibus means for CSRD, CS3D and the EU Taxonomy and how you should respond.

Read more

2025 Outlook: What lies ahead for climate and sustainability in financial services?

Here's what's front of our minds for 2025 based on our dialogue with, and work for, climate and sustainability leaders across financial institutions.

Read moreIs digital and AI delivering what your business needs?

Digital and AI can solve your toughest challenges and elevate your business performance. But success isn’t always straightforward. Where can you unlock opportunity? And what does it take to set the foundation for lasting success?