ESG is more than the defining challenge of our time. According to estimates from Bloomberg Intelligence, ESG assets are set to balloon from $35 trillion to $50 trillion by 2025. The growth has been spurred by record-breaking fund inflows amid concerns about climate change and other societal issues. The 20 largest banks have united, committing to deploy approximately $10 trillion in sustainable finance and towards the climate transition by 2030. And five banks have individually committed to deploy $1 trillion or more. The question that regulators and stakeholders will be asking is whether that huge wall of capital is actually making a difference in the world or is it being gamified.

‘Show me, not tell me'

This unprecedented commitment of capital towards ESG should be making a significant impact and driving scale adoption of new technologies, rewarding companies that are truly seeking to move the dial on ESG issues. The truth is that the evidence is mixed in the real economy. This is a problem because if that money isn’t targeted towards the companies that really are driving change, the business case for being sustainable starts to lose it shine. And if these new sources of sustainable capital are used to support business as usual rather than drive systematic change, socioeconomic and environmental value will be lost.

Pressure from stakeholders to increase transparency on ESG topics is growing. Stakeholders are starting to expect greater visibility, wanting to see the true impact of their investments, beyond greenhouse gas emissions reduction and board diversity. The EU SFDR / UK SDR and the FRC’s newest Stewardship Code, call for a ‘show me, rather than tell me’ approach. These regulations give more focus to ESG disclosures that support credibility, and the consequent actions needed to take to drive improvements.

For example, the SFDR and UK SDR consultation both require enhanced ESG disclosures from financial organisations of their sustainability impact. This is both at the entity and product level on a range of funds’ media platforms. Not only are companies required to demonstrate positive impact, but also show that they are not doing significant harm against other environmental objectives under the DNSH principle.

The FRC Stewardship Code in the UK requires transparency over the stewardship of investments. This transparency plays a fundamental role in providing confidence to stakeholders. However, the key to good stewardship, the monitoring, engagement and reporting surrounding the investment, is that it must be focused on the issues that are most material to long-term value.

Patience with greenwashing has run out

The above changes are not only a step-change which requires investors to measure, on the whole, previously overlooked factors but also penalises those who mis-sell their products. The SEC’s recent $1.5m fine of BNY Mellon for misusing green labelling for its funds underlines a new era of regulation for ESG information whereby finance can no longer ‘tell’ stakeholders they do good without ‘showing’ it credibly.

ESG frameworks and the metrics they drive are eyed by regulators globally under the objective of creating consistency and preventing greenwashing. Alongside the SEC’s game-changing fine, the FCA recently published a consultation on the prevention of greenwashing. Beyond this, some organisations have taken proactive action: for example, investment management firm Morningstar removed more than 1,200 funds with a combined $1.4tn in assets from its European sustainable investment list as they didn’t have sufficient evidence to support their inclusion in their Sustainable Investment list. In May 2022, the SEC stated that funds with “ESG” in their name would have to clearly define the term and also ensure that 80% of the assets in the fund adhered to that definition, an adaption of the existing Names Rule.

For asset owners, the challenge is that they are reliant on the asset managers to provide this data in a consistent and transparent way. Engagement between these two parties has historically been, at best, at arms-length. The Stewardship Code has changed that, with asset owners now asking for data which exposes the inner working of asset managers businesses to manage their fiduciary duty. Disclosures are designed to focus on good governance, and societal and environmental impact, which are critical factors for long-term growth. Not delivering the transparency expected by stakeholders could lead to significant outflows from asset owners, as well as increased regulatory scrutiny.

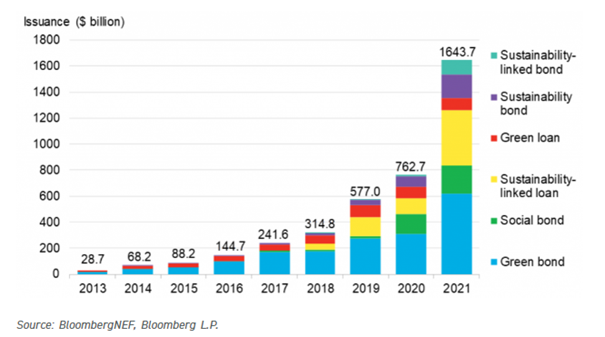

For banks, the risk of greenwashing is heightened with the new wave of ‘green financial products’, supporting these significant sustainable finance commitments. Whilst vehicles such as Sustainable Linked Loans (SLLs) stimulate much needed finance to the transition, they remain a work in progress in terms of their ability to drive sustainable outcomes. Inconsistency and a lack of transparency in sustainable finance raises concerns that the practice is open to widespread abuse.

"As the market for sustainable finance grows rapidly, sustainable loans reached a record $448bn at the end of the third quarter. Baringa’s analysis suggests that up to half of these loans could be open to greenwashing."

There is hope however – upcoming regulation, such as the EU taxonomy, will make the green/brown distinction clearer and help purposeful investors to better avoid greenwashing. The risk here is that they only take the ‘E’ into consideration and not the ‘S’ and the ‘G’. Factors such as whether a sustainability-linked loan would be classed as sustainable if it has negative social side effects are still being debated, although the EUs ‘Do No Significant Harm’ principles are helpful in this regard. The requirements and thresholds included in the taxonomy will be stringent and highly detailed when finalised, requiring rigorous data collection and consistent methodologies to address data gaps.

ESG as BAU

Achieving this level of transparency involves a significant change process in the way that asset managers and financial institutions have typically operated. It involves capturing good quality data from underlying investments and demonstrating that they are delivering on what they committed to their stakeholders.

In this ‘show me’ world, environmental and social outcomes need to follow the money that has supposedly gone into achieving those outcomes. This will uncover tricky dilemmas to resolve, particularly with the current cost of living crisis and the wider economic climate. However, a structured approach to ESG will enable businesses to make informed and insightful decisions, equipping them to be fit for future challenges in the new sustainable world.

Related Insights

When risks converge, do you know how your financial dominoes will play out?

Addressing the interconnection between risks isn’t just prudent; it's essential for firms to safeguard their financial stability and remain resilient in an increasingly unpredictable world. But how can organisations go about building that all-important view of interconnecting risks and their potential impacts?

Read more

Five ways to maximise return on investment from climate scenario analysis

Conducted effectively, climate change scenario analysis can unlock strategic insights, enhance business’ climate capabilities and meet regulatory requirements.

Read more

What are three facets of a credible climate disclosure programme?

With the introduction of new sustainability disclosure standards globally, companies are needing to increase the granularity of analysis and the specificity of their disclosures.

Read more

The great balancing act for superannuation funds

This article explores five challenges Chief Risk Officers should be aware of as they assist superannuation funds to secure long-term sustainable investments

Read more